Introduction

Collaborative endeavour remains an important component of global health research pursuits and innovation, yet existing structures meant to facilitate this collaboration often reinforce systemic inequities. Worldwide, research institutes are built on organizational frameworks that, while effective and sustainable for some, create significant barriers for the vast majority of early career researchers (ECRs), especially those seeking to tackle complex global health issues through purposeful involvement in the research enterprise.1 Within A Theory of Justice, John Rawls developed the concept of the “Veil of Ignorance,” characterized by designing just institutional arrangements by being ignorant of our position in society can help in efforts to ensure that the least advantaged members benefit from available resources.2 The concept is also applicable to research institutes by ensuring equitable structuring of opportunities to elevate the ECRs facing significant barriers to full access and participation. Despite the growing recognition and increasing calls for equity in global health research, the modus operandi of many research institutes systematically marginalizes ECRs, especially those from low-income and middle-income countries (LMICs).1

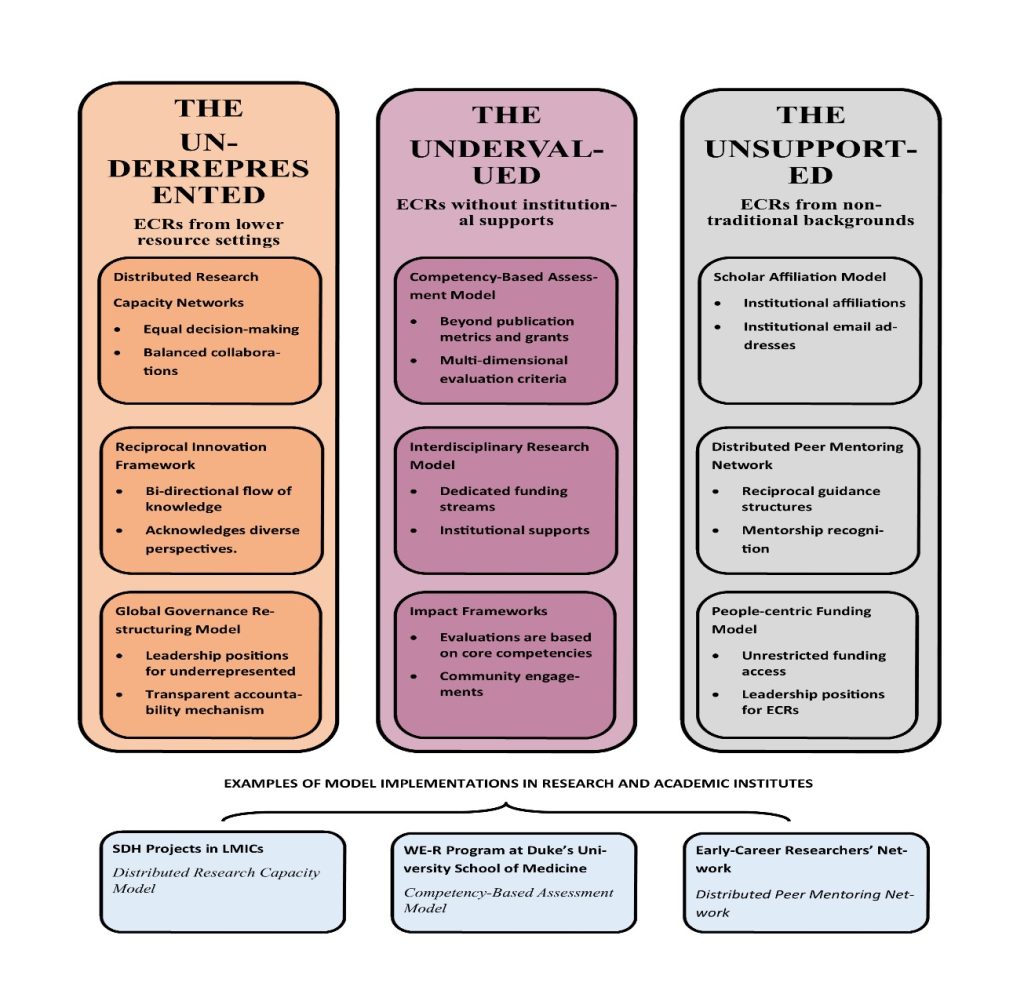

This essay approaches the topic from the perspective of LMICs by exploring innovative models that can be adopted by research institutes to enhance ECRs involvement in research institutes leveraging three distinct but interconnected strands of researchers facing barriers to full research participation and career progression. “The underrepresented” are defined by ECRs from research institutions in LMICs whose visibility is obscured, and voices are not included in global research conversations. “The Undervalued” considers ECRs whose intellectual contributions are systematically marginalized on the basis of their nontraditional background and, more broadly interdisciplinary approaches. “The Unsupported” refers to ECRs without strong institutional backing who navigate research careers in isolation without the benefits of traditional research support services. In the broad context of ECR’s participation in research institutes, inequities have never been more visible within these three dimensions and one way to address this issue could be to adopt a transformative model of involvement.

The Underrepresented

Historically, research institutes across the globe continue to concentrate visibility, power, and resources within the paradigm of high-income countries (HICs), creating a global hierarchy and inequities in which researchers from LMICs are tremendously underrepresented in leadership, driving research agenda, and research literature.3 Despite making up a striking 84% of the world population, researchers from LMICs are disproportionately underrepresented in global research publication and access.3 Authors from HICs, specifically, the USA and Western Europe account for an estimated 80% of publications in infectious disease journals.4 The African continent, for instance, produces an estimated 1% of the global research publications with the bulk of these publications emanating from South Africa, Egypt, and Nigeria.5,6 Incomplete access to research publications impedes scientific progress while encouraging back-door access to information. While HIC researchers are increasingly dominated in clinical trial research conducted in LMICs, findings from these studies are not consistently freely accessible to local researchers.7 For example, an estimated one-third of the 500 top-cited articles on emergency medicine between 2012 and 2016 were freely accessible.8 While the World Health Organization’s Health InterNetwork Access to Research Initiative (HINARI), Research4Life, and Open Access publishing offer free access to scientific literature, these initiatives are only available to researchers from the lowest-income countries, excluding the LMICs. Since the majority of research institutions in the LMICs struggle with subscriptions to scientific articles, authors circumvent insufficient access by overwhelmingly relying on illegal online research libraries such as Sci-Hub. For instance, from over one million scientific articles pirated annually, 69% of download requests come from LMICs.9 This profound imbalance transcends simple numerical underrepresentation, it highlights the deeper structural inequities in how the values attached to scientific contributions are prioritized and determined. Notable multifaced barriers such as limited research infrastructure including institutional support and laboratory facilities limit the underrepresentation of even the most talented ECRs from LMICs in global scientific discourse.1 In addition, attendance at international conferences is often limited by high funding costs precluding opportunities to participate in educational, networking, training, and promotional opportunities needed for career progression.1,4 Language barriers evident through the dominance of the English Language in HIC-based journals further obstruct the visibility of research conducted by these ECRs, thereby perpetuating repeated cycles of systematic exclusion and marginalization.

Moving towards innovative models, that address the baseline inequities alongside power dynamics while increasing representation, should be the priority. One model of a global research network that offers a transformative approach is the Distributed Research Capacity Network.10 In this model, research institutes are not envisioned as centralized entities but rather as hubs within a distributed global network where resources can be managed by different nodes in the network. Equal decision-making power would be distributed regardless of resource capacity, with dedicated resources managed collaboratively by each hub. The SDH-Net project on social determinants of health in LMICs fostered equitable South-North-South collaborations, knowledge management, research partnerships, exchange of researchers, and dissemination of research findings, particularly benefiting the ECRs leveraging this model.11

Reciprocal Innovation Framework is another global health research model with a critical role in restructuring the engagement of research institutes with underrepresented ECRs.12 Rather than following the white supremacist framework of “capacity building” that conceptualizes knowledge flows from HICs to LMICs and that quality institutions are lacking in the latter, this framework leverages a bidirectional approach to resource exchanges where the unique expertise and knowledge that emerges from these two contexts are recognized. The National Institute for Health and Care Research (UK) and Fogarty International Center – NIH have elements of this framework incorporated in their funding opportunities.13,14 Here, a bidirectional capacity building is fostered where LMIC institutions train their HIC counterparts on contextually appropriate research methodologies while the latter provide access to distant learning resources such as online libraries and statistical software.

The Global Governance Restructuring model is another transformative approach that fosters inclusivity and diversity at the most fundamental level—the decision-making process within an institution.15 The model reinforces the principles of representation and addresses existing institutional inequities—where research institutes are encouraged to implement inclusive governance structures where ECRs from historically marginalized institutions are included in the leadership positions. Under the leadership of Dr. Hannah Valentine, the implementation of this model in the US National Institutes of Health (NIH i.e. the largest funder of STEM research across the world) Distinguished Scholar Program – has drastically reduced barriers to recruitment of underrepresented ECRs in biomedical research and created more equitable opportunities for them.16

Figure 1. Transformative Models for Equitable Involvement of Early-Career Researchers in Research Institutes.

The Undervalued

Despite institutional rhetoric celebrating cross-boundary research and innovation, ECRs pursuing non-traditional research areas and methodologies continue to be severely undervalued by research institutions, particularly those in the LMICs.1 The term “undervalued” ECRs encompasses those without academic or professional experience, those adopting methodological approaches deviating from the conventional norms, and those working at disciplinary intersections in research-oriented settings. The systemic devaluations of ECR contributions not only worsen their academic precarity but also impede equitable research collaboration and scientific progress, as innovations often emerge from the intersection of diverse perspectives and experiences associated with these boundary-spanning roles.

The perceived undervaluation of ECRs manifests in several distinct ways. For instance, the promotional pathways and evaluation criteria consider traditional metrics including journal impact factors and acquisition of external funding for high-quality research, metrics that systematically disadvantage ECRs due to the limited/absence of publications in high-impact journals with high citations and long track record of independent grants.17 In addition to this, nonlinear career paths stand as a bane to the progress of ECRs as hiring committees display bias against them, despite the positive impact of diverse professional experiences on research output.18 According to one study, analysis of 53,194 résumés coupled with corresponding application forms of these candidates across 42 different organizations revealed a lower likelihood of recruiting applicants with deviated experience from the average i.e. either below or above.18 In their study, Vlasits et al. identified time and age as restrictions to access early-career funding for those who have taken the nonlinear path.19 For instance, the US NIH mandate the early-stage investigator status to 10 years of holding a terminal research degree.20 This policy has no considerations for career breaks taken for other non-research activities like caregiving, thereby affecting women and ECRs from underrepresented research institutions or backgrounds.

The Competency-Based Assessment Model which is similar to Impact Framework fits well with the evaluation and promotion of ECRs, which is not bound by conformity to the traditional academic model of publish or perish and funding acquisitions.21 In this model, core competencies driving research impacts such as experimental skills, collaboration and team science skills, stakeholder engagement, community engagement, methodological innovation and responsible conduct of research, knowledge translations, and technological development become the evaluation criteria for the promotion of ECRs. The Duke’s University School of Medicine has implemented this framework through its WE- (Workforce Engagement) R- (Resilience) Program for the promotion of clinical research professionals. Performance across various competencies was used as an eligibility determinant for tier advancements—which was ultimately linked with increment in salaries.22 This model has also been adopted by the Hungarian Academy of Sciences to address prevailing disparities in discipline-specific performance evaluation while facilitating the integrity of the advancement process.23

In a similar vein, the Interdisciplinary Research Model offer a promising dedicated organizational structure for ECR involvement, especially within research institutes that prioritize cross-boundary research. In this model, various evaluation metrics coupled with dedicated funding streams remain some of the institutional support for ECRs involved in interdisciplinary research.24 The Nigeria Implementation Science Alliance through its Model Innovation and Research Centres dedicated to multicentered clinical trial and implementation research has been able to foster collaborations between interdisciplinary researchers, healthcare professionals, academic institutions and policymakers.25 This serves as a replicable model for ECR involvement while creating an opportunity for methodological innovation.

The Unsupported

A growing cohort of ECRs are increasingly interested in working at the research institutes; however, the lack of stable institutional affiliations and infrastructural support are considered major challenges.1 These “Unsupported” researchers perceived as “Performing Monkeys” by Locke and colleagues are defined as those in precarious positions working temporarily for a short term (such as doctoral, post-doctoral, and independent researchers) without formal established ties to the concerned institutions.26 Over recent decades, this precarity has witnessed a sharp increase. In the academic institutions in the United States alone, the percentage of doctorate-holding nonfaculty researchers increased by 7.7% between 2017 and 2019, adding more than 2,100 doctorate-holding researchers outside of faculty tenure.27 Research institutes structure their models around formally employed and stable researchers, leaving those in unstable positions unsupported and without access to essential institutional resources and career development opportunities such as mentorship.

The global research landscape poses significant challenges to ECRs which transcend beyond instability. In some countries, especially in LMICs, postdoctoral researchers and principal investigators lack institutional affiliations, which limits opportunities to access critical research infrastructure such as subscription-based academic resources, laboratory space, and funding needed to facilitate career progression.28 In addition, difficulties in accessing grants become more peculiar to unsupported ECRs as grant eligibility criteria usually require institutional letters of support, creating a paradoxical barrier to accessing funding needed to improve research culture. In LMICs, limited access to research funding among the ECRs contributed to job insecurity while a decrease in non-contingent academic positions among doctorate-holding researchers in HICs has been attributed to a lack of structured mentorship1,28.

Supporting the unsupported ECRs necessitates rethinking how we define membership and allocate resources within the research institutes. One such innovative model is the Scholar Affiliation Model, where research institutes provide temporary affiliations and institutional support for independent researchers. This model, adopted and implemented successfully by the Ronin Institute for Independent Scholarships, allows the Ronin scholars the legal right to use the institutional affiliation and are provided with institutional email addresses for grant applications.29 The People-centric funding model at Howard Hughes Medical Institute is also worth replicating.30 This model works by providing unrestricted funding access to ECRs without the constraints of typical traditional funding pressures. Interestingly, through Canada’s Tri-Agency Approach, the Canadian government has created balanced funding for projects led by ECRs with emerging researchers occupying Tier 2 Canada Research Chairs positions.31

Another model of importance is the Distributed Peer Mentoring Network.32 In the context of research institutes, this model allows unsupported ECRs from underrepresented institutions to access academic resources. This model requires establishing a non-hierarchical virtual group where ECRs collaborate and mentor each other. Element of this model, through the Early Career Researchers’ Network implemented by the University of Liverpool, allows ECRs to improve their research skills and competence, identify funding opportunities, and advance their careers.33 The long-term Cross Institutional Mentoring Model involves forming structured mentorship relationships between mentor-mentee partnership across various institutions to provide them with sustained support, deviating from the traditional hierarchical mentoring model of mentor-protégé relationship. In this case, the mentor is a senior researcher and mentee is the ECR.34 Elements of this model has been initiated by the Consortium for Advanced Research Training in Africa (CARCA) where it facilitates ECRs’ access to interlinked networks with dedicated institutional support through mentorship and opportunities for career progression. These promising evidence-based results show that with successful implementation of these models, inequitable involvement of ECRs particularly in LMIC research institutes can be challenged to create sustainable research ecosystems and develop innovative solutions to global health problems.

Conclusion

While continued involvement in research institutes promises to advance research progress, current models in these settings historically perpetuate systemic inequities that worsen the existing complex global challenges faced by the underrepresented, the undervalued and the unsupported ECRs. When John Rawls envisioned equity, it was from the lens of “difference principle” where equities are justified when individuals are treated differently on the basis of their circumstances and needs. By systematically adopting and adapting the evidence-based models proposed in this essay such as Distributed Research Capacity Networks, Global Governance Restructuring Model, Competency-Based Assessment Model, and Distributed Peer Mentoring Network, research institutes can create promising paths to more equitable research involvement for all ECRs where they will be treated based on their circumstances and needs.

Implementing these models requires rethinking the operational modalities of research institutes, allocation of resources, and criteria for success evaluation. Current models, despite their implementation continue to reinvigorate repeated patterns of inequities where significant portions of ECRs are not served, thereby limiting scientific advancement. Research institutes especially those in LMICs are at a crossroads. Moving away from the hierarchical models requires a transformative change that considers structural modifications and places ECRs at heart for meaningful research involvement. Otherwise, research institutes especially those in LMICs risk repeating cycles of underrepresented, undervalued, and unsupported ECRs.

References

- Salihu Shinkafi T. Challenges Experienced By Early Career Researchers in Africa. Future Science OA. 2020;6(5). https://doi.org/10.2144/fsoa-2020-0012

- Rawls J. A Theory of Justice. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press; 1971.

- Gunawardena IPC, Retinasamy T, Shaikh MF. Is Aducanumab for LMICs? Promises and Challenges. Brain Sci. 2021;11(11):1547. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci11111547

- Mohamedbhai G. Promoting developmental research: A challenge for African universities. J Learn Dev. 2014;1(1).

- Uthman OA, Uthman MB. Geography of Africa biomedical publications: An analysis of 1996-2005 PubMed papers. Int J Health Geogr. 2007;6(46). https://doi.org/10.1186/1476-072X-6-46

- Tijssen RJW. Africa’s contribution to the worldwide research literature: New analytical perspectives, trends, and performance indicators. Scientometrics. 2007;71(2):303-327. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-007-1658-3

- Wemos. Clinical trials in Africa: The cases of Egypt, Kenya, Zimbabwe and South Africa [Internet]. Issuu; 2018 [cited 2025 May 16]. Available from: https://issuu.com/stichtingwemos2017/docs/jh_wemos_clinical_trials_v5_def

- Al Hamzy M, de Villiers D, Banner M, Lamprecht H, Bruijns SR. Access to Top-Cited Emergency Care Articles (Published Between 2012 and 2016) Without Subscription. West J Emerg Med. 2019;20(3):460-465. https://doi.org/10.5811/westjem.2019.2.40957

- Till BM, Rudolfson N, Saluja S, Gnanaraj J, Samad L, Ljungman D, et al. Who is pirating medical literature? A bibliometric review of 28 million Sci-Hub downloads. Lancet Glob Health. 2019;7(1):e30-e31. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30388-7

- Rho MJ, Park J. An Investigation of Factors Influencing the Postponement of the Use of Distributed Research Networks in South Korea: Web-Based Users’ Survey Study. JMIR Form Res. 2023;7:e40660. https://doi.org/10.2196/40660

- Cash-Gibson L, Guerra G, Salgado-de-Snyder VN. SDH-NET: a South–North-South collaboration to build sustainable research capacities on social determinants of health in low- and middle-income countries. Health Res Policy Syst. 2015;13:45. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12961-015-0048-1

- Sors TG, O’Brien RC, Scanlon M, Bermel LY, Chikowe I, Gardner A, et al. Reciprocal Innovation: A New Approach to Equitable and Mutually Beneficial Global Health Research and Partnership [preprint]. 2021. DOI: 10.21203/rs.3.rs-1135284/v1.

- Fogarty International Center. Global Health Reciprocal Innovation [Internet]. 2024 [cited 2025 May 12]. Available from: https://www.fic.nih.gov/About/center-global-health-studies/Pages/global-health-reciprocal-innovation.aspx

- National Institute for Health and Care Research. Global health research (ghr) funding committees co-chair person specification [Internet]. 2022 [cited 2025 May 13]. Available from: https://www.nihr.ac.uk/global-health-research-ghr-funding-committees-co-chair-person-specification

- Eilstrup-Sangiovanni M, Westerwinter O. The global governance complexity cube: Varieties of institutional complexity in global governance. Rev Int Organ. 2022;17:233-262. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11558-021-09449-7

- National Institutes of Health. Statement on the Retirement of Dr. Hannah Valantine [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2025 May 12]. Available from: https://www.nih.gov/about-nih/who-we-are/nih-director/statements/statement-retirement-dr-hannah-valantine

- Salihu Shinkafi T. Challenges experienced by early career researchers in Africa. Future Sci OA. 2020;6(5):FSO469. https://doi.org/10.2144/fsoa-2020-0012

- Wechtler HM, Lee CISG, Heyden MLM, Felps W, Lee TW. The nonlinear relationship between atypical applicant experience and hiring: the red flags perspective. J Appl Psychol. 2022;107(5):776-794. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000953

- Vlasits AL, Smith ML, Maldonado M, Brixius-Anderko S. Supporting nonlinear careers to diversify science. PLoS Biol. 2023;21(9):e3002291. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.3002291

- National Institutes of Health. Revised New and Early Stage Investigator Policies [Internet]. NIH Guide. 2008 Oct 31 [cited 2025 May 16]. Available from: https://grants.nih.gov/grants/guide/notice-files/NOT-OD-09-013.html

- Škrinjarić B. Competence-based approaches in organizational and individual context. Humanit Soc Sci Commun. 2022;9:28. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-022-01047-1

- Society of Research Administrators International. Professional Development for Clinical Research Professionals: Implementation of a Competency-Based Assessment Model [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2025 May 15]. Available from: https://www.srainternational.org/blogs/srai-jra1/2020/09/29/professional-development-for-clinical-research-pro

- Csomós G. Introducing recalibrated academic performance indicators in the evaluation of individuals’ research performance: A case study from Eastern Europe [preprint]. arXiv:2006.13321. 2020. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2006.13321

- National Institutes of Health. Interdisciplinary Research [Internet]. 2024 [cited 2025 May 16]. Available from: https://commonfund.nih.gov/interdisciplinary-research-ir

- Olawepo JO, Ezeanolue EE, Ekenna A, Ogunsola OO, Itanyi IU, Jedy-Agba E, et al. Building a national framework for multicentre research and clinical trials: experience from the Nigeria Implementation Science Alliance. BMJ Glob Health. 2022;7(4):e008241. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2021-008241

- Locke M, Trudgett M, Page S. Australian Indigenous early career researchers: unicorns, cash cows and performing monkeys. Race Ethn Educ. 2023;26(1):1-17. https://doi.org/10.1080/13613324.2022.2114445

- Arbeit C, Yamaner MI; National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics (NCSES). Trends for Graduate Student Enrollment and Postdoctoral Appointments in Science, Engineering, and Health Fields at U.S. Academic Institutions between 2017 and 2019. NSF 21-317. Alexandria, VA: National Science Foundation; 2021. Available from: https://ncses.nsf.gov/pubs/nsf21317/

- Kent BA, Holman C, Amoako E, Antonietti A, Azam JM, Ballhausen H, et al. Recommendations for empowering early career researchers to improve research culture and practice. PLoS Biol. 2022;20(7):e3001680. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.3001680

- Di Maio P. Ronin Institute for Independent Scholarship [dataset]. figshare; 2025. https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.28970018.v1

- Ford C. Science has a short-term memory problem [Internet]. 2024 [cited 2025 May 16]. Available from: https://www.vox.com/future-perfect/370681/science-research-grants-scientific-progress-academia-slow-funding

- Canada Research Coordinating Committee. Supporting early career researchers [Internet]. Canada.ca; 2025 Mar 6 [cited 2025 May 14]. Available from: https://www.canada.ca/en/research-coordinating-committee/priorities/early-career-researchers.html

- Cox A, Blaha C, Cunningham B, Hunter A-B, Ivie R, Phan-Budd S, et al. Distributed peer mentoring networks to support isolated faculty. J Fac Dev. 2021;35(1):43-48.

- University of Liverpool. Early Career Researchers’ Networks [Internet]. 2025 [cited 2025 May 12]. Available from: https://www.liverpool.ac.uk/researcher/staff-resources/ecr-network/

- Hurtado S, González RA, Galdeano EC. Organizational Learning for Student Success: Cross-Institutional Mentoring, Transformative Practice, and Collaboration Among Hispanic-Serving Institutions. In: Hispanic-Serving Institutions. Routledge; 2015. p. 177-195.

- Consortium for Advanced Research Training in Africa. Building a vibrant multidisciplinary African Academy that leads world-class research [Internet]. 2025 [cited 2025 May 16]. Available from: https://www.cartafrica.or

Leave a Reply